- Home

- Caroline Kington

A Tangled Summer Page 2

A Tangled Summer Read online

Page 2

The telephone rang, interrupting her gloomy reverie. Jenny answered. ‘Marsh Farm… Jenny Tucker… Yes…yes, she’s right here. Elsie, it’s for you. It’s a Mr Ian Webster. He says he’s an old friend; he needs to have a word with you, urgently…’

With some surprise, it being barely nine o’clock, Elsie took the call.

* * *

The magistrates’ court had been built next to a school, and on this hot Thursday morning, the sound of childish laughter and shouts from the playground mingled with the noise of traffic, and, unfettered, drifted in on shafts of sunlight through the bars of the open windows.

Charlie Tucker licked his lips. He had never been in a court before. He had been in a police cell before; had been ticked off by a senior policeman a couple of times for drunken behaviour; and had collected a number of speeding fines; but he had never before been in a magistrates’ court and he was not enjoying the experience, not one little bit. What made it worse was the presence of his grandmother in the public gallery. She had entered just as he took his place in the dock, and at the sight of her, his knees had given way and he had sat down.

The old lady had not looked at him, but stared ahead; her face, which betrayed no expression, was thin and weathered, devoid of make up. The other occupants of the public gallery lolled about in various combinations of T-shirts, tracksuit bottoms and trainers, their flabby bodies and pale, pudgy faces liberally tattooed, pierced and bejewelled. She, however, looked as if she had stepped across a time warp. Her iron-grey hair was pinned up under a small straw hat and she was dressed in a long-sleeved, cream blouse and a tweed skirt, over which, in spite of the warmth of the day, she wore a khaki-green, loden waistcoat. She looked what she was: every inch a countrywoman.

Charlie had groaned inwardly as he got back to his feet. He had thought he had been successful in keeping his appearance before the Beaks well away from his family’s notice. Of them all, the last person he wanted to witness his humiliation was his grandmother. Throughout the proceedings he avoided looking at her, but as he stuttered through his explanations and apologies, he was aware of her gimlet eyes and pursed lips. It was her presence, rather than the faintly bored looking trio who were sitting on the Bench, which caused him to perspire freely, and to lose that cocky insouciance which he normally adopted in times of difficulty and which, on this occasion, would not have done him any favours.

The magistrates left the courtroom to mull over their decision. They were gone only a few minutes, but already it seemed like an eternity to the young man in the dock. He was unused to wearing a suit and it showed. He was tall and muscular and his jacket barely fitted. He had given up trying to button up his shirt at the collar and tried to disguise the fact with the only tie he’d been able to find, a joke Christmas present from his sister, decorated with bright yellow ‘Smiley’ faces. He was a good-looking man, with a thick head of hair, shiny with Brylcreem, and a pair of carefully cultivated mutton-chop whiskers, which framed his lean, weather-beaten face. He had thought about shaving them off that morning, to try to improve the impression he would make, but he loved his whiskers and the realisation that if he removed them, he would have two ridiculously large white shadows in their place saved them. Under normal circumstances, his brown eyes were merry, his appearance cocky, and life, for him, was a good laugh. Today, however, his cockiness had evaporated, and he sat dejectedly, shoulders drooping, listening to the sounds of the children playing outside.

‘Its torture, that’s what it is...’ the defendant thought bitterly, ‘I bet it’s done deliberately… The Beaks go out, give the teacher a ring ‘Oh, is that the teacher? We’ve got a nice one in the dock at the moment. We’re just off to have a cup of coffee, so send the little kiddies out please – lots of noise and laughing, that’s the ticket! That should make him feel a whole lot worse…’ Well too bloody right it does! And what’s Gran doing here? How did she find out? Bloomin’ ’eck, I’m really going to be for it!’ And Charlie Tucker, thrirty-two, a farmer, rather more by birth than inclination, sat on the edge of his seat in the dock and fixed his eyes steadfastly on the floor in an effort to avoid any chance contact with the basilisk glare from ‘her’ in the public gallery.

The door to the retiring room opened and he jumped, in spite of himself.

The clerk, young, blond and bored, scarcely glanced up from sorting through a large pile of case notes. ‘Stand, please’.

A plump young woman in a tight blue dress, with mousy hair, not much older than Charlie himself, was followed by the Chairman, stout, middle-aged and balding, in a pin-striped suit with a florid yellow handkerchief drooping from his breast pocket, and by the third magistrate, a West Indian, in his late thirties, dressed in a sober dark suit and dark shirt. Charlie had thought he looked pretty cool, a kindred spirit, and during the hearing had addressed his comments chiefly to him, hoping to engage his sympathy. He searched his face now, for some sign of comfort, as the magistrates took their seats. There was none. His face impassive, the magistrate glanced at him with complete indifference before turning to listen to the chairman.

‘Well, Mr Tucker, you’ve told the court you’d had a “bit to drink” and you climbed up onto the bear for a “bit of fun’’.’ With obvious disdain, the magistrate viewed Charlie over his half-moon specs, ‘It wasn’t much fun, though, was it, when you couldn’t get down? And it wasn’t much fun for the police or the fire brigade when they had to rescue you. These services are stretched enough as it is, without having to rescue a drunk from the consequences of his folly...’

The clerk stretched out a finger, pressed a button and the windows whined shut, cutting off the jubilant sounds of the playground that were threatening to drown out the chairman’s homily.

‘You were fortunate that the bear you chose to mount, above the lintel of the pub, was sufficiently robust to withstand your weight, and that neither you, nor it, nor any member of the public, suffered any injury as the result of your absurd prank. Had that been the case, you would have appeared before us on a much more serious charge. Don’t you think, Mr Tucker, that at the age of thirty-two, it is time you grew up?’

The magistrate paused to emphasise his point, allowing the old lady’s harrumphed agreement to add to Charlie’s discomfort, before dismissing him with, ‘We note your evident remorse and your embarrassment; we have given credit for your early guilty plea and for your apology. We are going to dispose of this by way of a fine. You will pay the court seventy pounds and, taking account of your lack of means, you will make a contribution of twenty pounds towards costs.’

* * *

‘Ninety quid! Blimey, Charlie. Where you gonna find ninety quid?’ Lenny Spinks, Charlie’s partner in crime, hands and face smeared with grease, dressed in filthy blue overalls, sleeves rolled up above his elbows, arms liberally tattooed, and long, streaky-blond hair tied back in a ponytail, stared up at Charlie.

Lenny was the only employee of Marsh Farm, and part-time at that. He had been fixing a tractor engine on the cracked and weedy concrete forecourt of an old barn that flanked the central yard of Marsh Farm when Charlie’s battered white van had screeched to a dusty halt and a disconsolate Charlie had climbed out.

‘They let you pay it off weekly. But Lenny, that weren’t the worst of it. You’ll never guess who turned up in court?’

Lenny, whose imagination was not the strongest in the world, looked blank. ‘Steve? Yer mum? Ali?’

Charlie gloomily shook his head, ‘Nah, if it’d been any of them, even Alison, it wouldn’t be so bad. Stephen would bellyache about the fine; Mum’d just be glad I didn’t fall off the flaming bear; and Ali’d just make lots of clever-clever, sarky comments about how her big brother can’t hold his drink and that riding a stone bear is the closest I’d ever get to mounting anything on four legs. No, it was Gran, Lenny.’

‘Elsie? How did she find out?’

‘God knows. Probably looked into her cry

stal ball or consulted her tea leaves, or whatever them witches do. Her nose is into every blooming pie; she knows everything that goes on, no matter what I do to stop her finding out stuff. God, she makes me feel about six inches tall!’ And he relapsed into a depressed silence.

‘Did she say anything, after?’

‘No.’ Charlie sighed. ‘This magistrate said… What a pompous old git… He said…well, it don’t matter what he said…but then I heard Gran suck in her breath and I knew I was for it. She’d left the courtroom before I’d even left the dock.’

Lenny was curious. ‘What did he say then?’

‘Doesn’t matter. Thing is, though, Gran is mad at me and she’ll be plotting something. Courts don’t take that into consideration, do they?’

‘What?’

‘Mad old grandmothers who can make your life hell if they choose to.’

‘I don’t know why you don’t tell her where to get off. After all, you run Marsh Farm, you and Steve. It’s the sweat of your labours what puts the jam on her bread…’

Charlie gloomily pulled at one of his sideburns, ‘True enough me old sparkplug, but you’re forgetting one tiny little detail: she owns half the farm. If I don’t jump to her tune, she’d probably cut me out and leave her share to Ali – they’re as thick as two thieves – and where would that leave me?’

‘Working for your sister?’

‘Over my dead body, mate!’

Stephen Tucker, emerging from the milking parlour where he had been struggling with repairs to a pump that should have been replaced years ago, looked across the yard and saw his older brother by the tractor, in conversation with Lenny Spinks. Nothing unusual in that, Lenny worked mainly for Charlie. No, what caught his attention was the sight of his brother in a suit. The last time he could remember Charlie in a suit was when he was best man at Lenny’s marriage to Paula, some six years ago. Before that, it was at their Dad’s funeral, and that was ten years ago now.

He crossed the yard to join them. It was nearly midday and the continuing heat had succeeded in turning the usually muddy yard into a dust-bowl. Dust had settled on everything and it felt as if it had taken him twice as long to clean up after milking. He felt fractious, and an ill-tempered frown marred his usually amiable face.

Two years younger than Charlie, Stephen, compliant, docile and cautious, was the antithesis of his brother. Physically, he was not quite as tall, although neither had reached the six-foot height of their father, something both boys had aspired to when younger. Their colouring was similar; but Stephen’s mop of chestnut brown hair was cut short and he was completely clean–shaven, his complexion was more ruddy than his brother’s, and he was well-covered, if not chubby, where Charlie was lean.

‘Hey, Charlie, what’s with the cloth? You off to a funeral or summat?’

Lenny, who was considerably shorter than either brother, smirked up at him, ‘His own, by his reckoning…’

Stephen didn’t much like Lenny Spinks.

As a child, Stephen had trotted admiringly in Charlie’s wake, a willing partner in his charismatic brother’s madcap schemes, often unfairly taking the lion’s share of the blame when things went wrong. Then, in his teens, Charlie discovered motocross and Lenny Spinks, and Stephen was no longer needed. The two boys drifted apart until Stephen was twenty, when Jim Tucker, his father, was found face down on the silage clamp, dead from a massive heart attack.

Gran owned half the farm, and her son had left his share equally between his three children. Alison was only seven at the time of his death, so it fell to Charlie and Stephen to shoulder the responsibility for running the farm, which they did, reflecting their inclinations and dispositions. Charlie took over all the arable cultivation; Stephen took care of the dairy herd and the milk production, and Lenny, who was a few years older than Charlie and therefore more versed in the ways of the world, was drafted in by Charlie as a hired hand, ‘him bein’ a whiz with machinery an’ all.’

Marsh Farm was not a large or profitable enterprise, and Charlie and Stephen were not particularly efficient farmers, but they muddled along, bumping into debt and out again, more by chance than design. But Charlie had ambitions. Full of unchannelled energy, he was always coming up with some moneymaking enterprise to which Lenny was usually privy. These schemes were designed to pluck the farm out of the red, but somehow they always seemed to leave them no better off and, more often, the poorer.

Seeing Charlie in a suit and in close conversation with Lenny, therefore, immediately roused Stephen’s suspicions.

‘What are you to up to then?’ he demanded, grumpily. ‘I thought you were starting on the barley today. You’re leaving it a bit late, ain’t yer? There’s no way I’m going help you out, so let’s get that clear for a start. We’ve started rehearsals this week and I’ve promised Mrs Pagett I’ll be there…’

In the same year Jim Tucker died, Stephen had discovered Amateur Dramatics. Or rather, it had discovered him, and ever since then, every spare moment was spent in its service.

‘Don’t worry, I wouldn’t dream of depriving your little society of its star turn.’ Charlie started to walk towards the house. ‘I’ll just get into my overalls, Lenny, an’ I’ll be with you. With any luck, we can work on till dusk; weather’s looking good.’

‘Okay, boss. Hey, I can see your Gran’s car comin’ down the track!’

And to the surprise of his brother, Charlie fled into the house, but Stephen did not linger to question Lenny. He had his own reasons for not wanting to come face to face with his Gran that morning, and disappeared off the scene almost as quickly as Charlie.

2

Alison sat in the window of her bedroom, nursing a headache and watching the scene in the yard with a scowl. ‘It’s bad enough being stuck here all summer,’ she thought bitterly, ‘but not to be able to go to the movies, or bowling, or clubbing... It’s so humiliating.’

The problem, as always, was lack of money, and for that, Alison blamed her brothers.

‘Ali, it’s gonna be wicked – we’ve got the rest of the summer sorted.’ Hannah had phoned her that morning to continue the conversation of the night before. ‘And with any luck, there’ll be a massive disco to finish it off… Nick’s been given a card by some guy who might employ him – he says he heard of these events. Think of it, Ali…beating your brains out to the music… They line up really good DJs… It’ll be so cool – boogying the whole night away, swigging bottles of Ice… Ali, if Nick’s right, we can’t miss it!’

‘Of course not,’ Alison had said. ‘No probs. Can’t wait.’ And when Hannah had rung off, Alison had gone in search of her mother and her monthly allowance.

‘I’m sorry, dear,’ Jenny had said helplessly, her eyes streaming from the pile of onions she was chopping. ‘There just isn’t any spare cash this month. Stephen says the milk cheque is right down because of that batch which got contaminated when the pump broke, so he can’t spare anything; and Charlie says, what with harvesting this month, he’s going to need all the spare cash he’s got to pay for Lenny’s extra hours.’

Her two brothers were meant to take it in turns to fund her monthly allowance, and, in fact, what Charlie had said to his mother was, ‘It’s Steve’s turn to find her allowance. No way am I going to give the kid money she ain’t earned when it’s not my turn. Nose permanently in a book... What good is that? Bloomin’ hell, she should get herself a job… I did when I was her age.’

Jenny had remonstrated feebly, ‘Now, Charlie, you know it’s her exam year. It’s important she works at her books and does well. You want her to go to the university, don’t you?’

‘It won’t stop her from comin’ to me for cash I ain’t got,’ came the morose reply, and Jenny had left, empty-handed.

When Alison learned form her mother that she would not be able to have her allowance for August, she had stared at Jenny in disbelief, then exploded, stormed out

of the kitchen and had gone back up to her bedroom, where she glowered down on her unsuspecting brothers in the yard.

‘They’re useless, absolutely useless! God knows how I’m going to afford to go to university at this rate!’

Engulfed by self-pity, she went back to her desk and the biology project she had been trying to finish when Jen had phoned.

She angled the magnified glass of the make-up mirror. Stephen had given it to her last Christmas and she had placed it on the corner of her desk so that she could monitor the progress of any eruptions. She always did this when she felt gloomy; it made her feel satisfyingly worse. As it happened, her skin was relatively clear, so there was no satisfaction to be had from squeezing blackheads.

Morosely, she stared at her distorted reflection. Unlike Charlie and Stephen, who had inherited their father’s brown hair and brown eyes, she shared her mother’s fair colouring. She wore her hair long, and she had a small pointed chin, high cheekbones and intense green eyes. Her eyes were greener than her mother’s and her features altogether sharper and more restless. She resembled Elsie in stature, but she was still sufficiently like her mother for it to be remarked upon, far too often for Alison’s liking. She loved her mother; she just didn’t want to be like her; no way!

‘She always does their dirty work for them; she’s putty in their hands!’ Alison spat at her reflection. ‘She should stand up to them; she’s such a bloody doormat. Gran’s right.’

In fact, Alison was always defending Jenny against accusations of a similar sort from Elsie Tucker, but on this occasion, she felt Jenny had let her down.

‘It’s not fair!’ Alison said to her reflection for the umpteenth time. ‘If I haven’t any money, then I can’t go out; and if I can’t go out, I’ll never meet anybody. I’ll die a virgin!’

At seventeen, Alison had got through a number of boyfriends, none of them particularly serious and none of them had given rise to the level of passion that, in her dreams, she felt should be the precursor to her first sexual experience. By the end of the previous term she was aware that she was becoming one of a rapidly decreasing number not to have had sex. While this did not particularly worry her, she did not want to be identified as a saddo, or a reject. Her place in her group of friends was unassailable when it came to talking about music, or films, or politics, or even fads of fashion; but when it came to discussing what it was like…she felt less than fully integrated and had to fall silent.

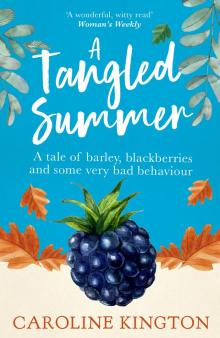

A Tangled Summer

A Tangled Summer